It was December 11, 1777.

The British – under the leadership of General William Howe – occupied the City of Philadelphia – the capital of a new nation striving to survive – and nearby communities.

The Continental Army – the army of the United States under the leadership of General George Washington – was in the Village of Whitemarsh. Today, we call that area “Fort Washington”.

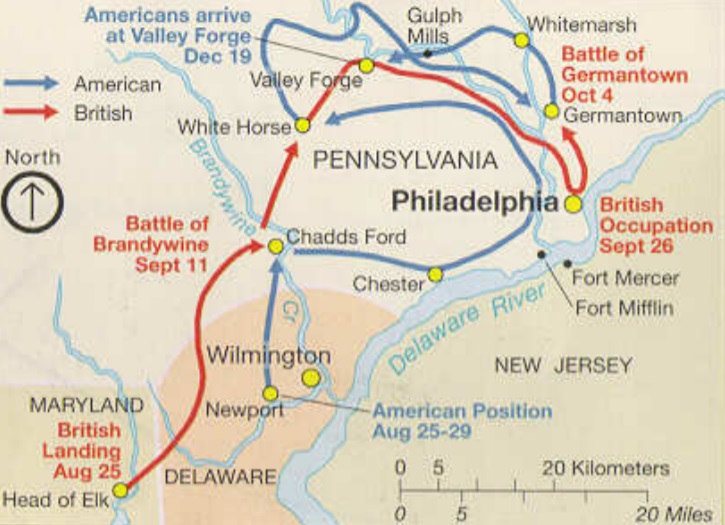

Battles had taken place in the previous months in Brandywine and Germantown.

The City of Philadelphia, at that time, was roughly what we call “Center City” today.

The County of Philadelphia was much larger at that time as compared to today – Montgomery County was part of Philadelphia County in 1777.

Plymouth Township, Whitemarsh Township, Upper Merion Township, and Lower Merion Township all were municipalities within Philadelphia County.

Matson’s Ford was located at a crossing – a ford – across the Schuylkill where the Matson family had placed piles of rocks so that people could cross the river.

The top photograph is a view of the Schuylkill looking downstream from Matson’s Ford in 2002.

The names of both “Matsonford Road” and “Ford Street” come from that river crossing.

Conshohocken and West Conshohocken did not exist as distinct communities in 1777.

General Washington made the decision to move the Continental Army to an area further west from the City of Philadelphia. His goal was to find a safe, secure place for the army to spend the winter of 1777-78.

That place eventually turned out to be Valley Forge.

To get the troops from Whitemarsh, General Washington made the decision to have the troops cross the Schuylkill at Matson’s Ford.

On the same date – December 11, 1777 – Major General Charles Cornwallis led part of the British troops out of the City of Philadelphia (Center City) into the countryside to forage in Lower Merion Township. In many cases, “forage” meant taking wood and hay for use by the armed forces.

Neither army apparently knew that the other was converging in the same place at the same time.

It was December 11, 1777.

The Battle of Matson’s Ford began and ended on that date.

There were two aspects to this battle.

One involved the Pennsylvania Militia that had been sent into what is now Lower Merion Township to secure that area.

The second involved the main Continental Army as it crossed the Schuylkill at Matson’s Ford.

The Pennsylvania Militia, under the leadership of General James Potter, engaged the British in Lower Merion Township.

But the battle did not go well for the Americans. Some members of the Pennsylvania Militia fled the battlefield. Some dropped their weapons as they ran from battle.

According to a report from the Valley Forge Tourism and Convention Board, “The militia flees, discarding their weapons in panic” as they retreated through Gulph Mills and Upper Merion Township.

The British stopped their pursuit in the hills of West Conshohocken. This allowed the Pennsylvania Militia to escape to fight another day.

As this was happening, the main Continental Army was moving from what we know of today as “Fort Washington” to the river crossing in what we call “Conshohocken” today.

According to a news article dated December 10, 1970, in The Daily Intelligencer, a flyer issued by the Montgomery County Tourist Bureau described the route taken by the American Revolutionary soldiers as they left Whitemarsh in December of 1777: “The Continental Army left [Fort Washington] early December 11, 1777, headed for Gulph Mills. The route was west on Skippack Pike (Route 73) to Butler Pike. The command turned left to march through Cold Point, Plymouth Meeting, Harmonville and to Matson’s Ford at the Schuylkill in Conshohocken.”

Under the leadership of General John Sullivan, hundreds of the men in the main Continental Army crossed the Schuylkill at Matson’s Ford. The troops had used wood from their wagons to create a make-shift bridge for the crossing.

These troops soon realized that the area was not safe with the British in command on the hills of what we call today “West Conshohocken” and the surrounding area.

According to the flyer from the Montgomery County Tourist Bureau that was quoted in The Daily Intelligencer, there were “4,000 mounted British troops” in the hills of West Conshohocken.

The encounter with the British troops caused General Washington to change his plans. According to a news article in The Times Sunday Special dated October 18, 1891, “It was Washington’s intention that the army should pass over the Schuylkill at Matson’s Ford, where a bridge had been laid. But when the First Division and a part of the Second had passed over they found a large body of the enemy under Lord Cornwallis possessing themselves of the heights on both sides of the road heading from the river and the defile called the gulf [Gulph Mills]. This unexpected event obliged such of the troops as had crossed to repass the river, and the army was then ordered to march to the Swede’s Ford [Norristown], three or four miles higher up the Schuylkill, where they went into camp for the night.”

As noted in that news article, the Americans that had just crossed the Schuylkill retreated back across the same make-shift bridge into what we now of today as “Conshohocken”.

After some period of time, the British left the hills of West Conshohocken went back to the City of Philadelphia.

According to a news article in Graham’s Magazine in 1854, one officer and seventeen men died on the American side during the Battle of Matson’s Ford.

From the ill-fated crossing at Matson’s Ford, the American troops that had retreated to what we call today “Conshohocken” went up what is today known as “Fayette Street” and “Butler Pike” to the Ridge Road (today’s Ridge Pike).

The Continental Army then marched through Plymouth Township to encamp that night at Swede’s Ford (Norristown). The troops would spend that evening there and cross the Schuylkill on December 12, 1777, to go to Gulph Mills. After about six days in Gulph Mills, the Continental Army then moved on to the winter encampment at Valley Forge.

In a news article dated August 7, 1933, in the Altoona Tribune, the headline indicated that the Battle of Matson’s Ford was called a “Hollow Victory” because neither side – not the British and not the Americans – won the battle.

“Both sides were equally terrified by the sudden and terrible appearance of the enemy, and each fled, leaving no one to take possession of the hard-won field!”

Regarding the actions of General Potter at the Battle of Matson’s Ford, a news article dated April 10, 1896, in the Lewisburg Journal stated that “He was present at the Battle of Matson’s Ford, now Conshohocken, in December [of 1777], and here became involved in a controversy with General [John] Sullivan, whose failure to appear at the proper time, destroyed the plans of the generals. Of this battle [General George] Washington wrote to Congress: ‘The enemy were met in their advance by General Potter, with part of the Pennsylvania militia, who behaved with bravery and gave them every possible opposition, till he was obliged to retreat from their superior numbers.’”

Some members of the Pennsylvania Militia who did not behave with bravery were held responsible for what the leaders of the army saw as their reprehensible actions at the Battle of Matson’s Ford. A court martial was held “to try such men as threw away their arms and equipments at the Gulf Mills [Gulph Mills], in order to facilitate their escape,” according to a news article in Graham’s Magazine in 1854. “Some were sentenced to be publicly whipped, which sentence was carried into effect, and caused much disturbance in camp.”

The British reported similar events, but with different wording.

(Yes, newspapers in England reported on activities of the war in the American colonies – including in communities throughout the Freedom Valley.)

Jackfon’s Oxford Journal in Oxfordshire, England, reprinted a letter from General Sir William Howe to an official with the British government at Whitehall in London. The actual letter from General Howe was dated December 13, 1777, and reported to Whitehall on January 18, 1778. The letter was then reprinted in a news article dated January 24, 1778, in this newspaper.

A portion of that letter – with the English language as in place in 1777 – reported that “The Enemy [that’s the American revolutionaries under the leadership of General Washington] having quitted their Camp at White Marfh fome Hours before Lord Cornwallis marched from hence, his Lordfhip met the Head of their Army at a Bridge they had thrown over the Schuylkill, near to Matfon’s Ford, about three Miles below Swedes Ford, and fifteen Miles Diftance from hence. Over this Bridge the Enemy has paffed eight hundred Men, who were immediately difperfed by his Lordfhip’s advanced Troops, obliging Part of them to re-crofs it, which occafioned fuch an Alarm to their Army, that they broke the Bridge, and his Lordfhip proceeded to forage, without meeting any Interruption.”

The translation of this section of the news article is as follows:

“The Enemy [that’s the American revolutionaries under the leadership of General Washington] having left their Camp at Whitemarsh some Hours before Lord Cornwallis marched from hence [City of Philadelphia], his Lordship met the Head of their Army at a Bridge they had thrown over the Schuylkill, near to Matson’s Ford, about three Miles below Swedes Ford [today’s Norristown], and fifteen Miles Distance from hence [City of Philadelphia]. Over this Bridge the Enemy has passed eight hundred Men, who were immediately dispersed by his Lordship’s advanced Troops, obliging Part of them to re-cross it, which occasioned such an Alarm to their Army, that they broke the Bridge, and his Lordship proceeded to forage, without meeting any Interruption.”

A similar, if not exact, news article was also printed in The Leeds Intelligencer in West Yorkshire, England, on January 27, 1778.

Today, there are almost no lasting elements that remain from the Battle of Matson’s Ford.

The river crossing is known today as “Matsonford” rather than “Matson’s Ford”.

A concrete bridge takes traffic over the Schuylkill rather than individuals walking on rocks in the water or an army moving materiel over pieces of wood from wagons.

One element that does remain today is the name “Rebel Hill”. It was likely that December 11, 1777, was the day that “Rebel Hill” got its name. From the British.

They saw the rebels – the Americans fighting a revolutionary war – in that area. Thus, “Rebel Hill”.

Sullivans Lane in West Norriton Township and Lower Providence Township as well as Sullivan Boulevard in Lower Providence Township were named after General Sullivan. Potter County in northern Pennsylvania was named in honor of General Potter.

In a few days, we’ll highlight the first official Thanksgiving proclaimed by the new nation. That event took place in Gulph Mills during the journey of the Continental Army from Whitemarsh to Valley Forge.

The photograph of Matson’s Ford is provided courtesy of the National Park Service, 2002.

The photograph of General George Washington is provided courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1800.

The photograph of Major General Charles Cornwallis is provided courtesy of Clare College, 1795.

The photograph of General John Sullivan is provided courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1776.

The map of the Philadelphia Campaign is provided courtesy of the National Park Service, 2002.

Do you have questions about local history? A street name? A building?

Your questions may be used in a future news column.

Contact Richard McDonough at freedomvalleychronicles@gmail.com.

© 2018 Richard McDonough