The Freedom Valley is filled with a number of structures and sites that have historical significance. Significance of a local, regional, and national nature. A number of these buildings can be found within walking distance of the intersection of Butler Pike and Germantown Pike in the Village of Plymouth Meeting.

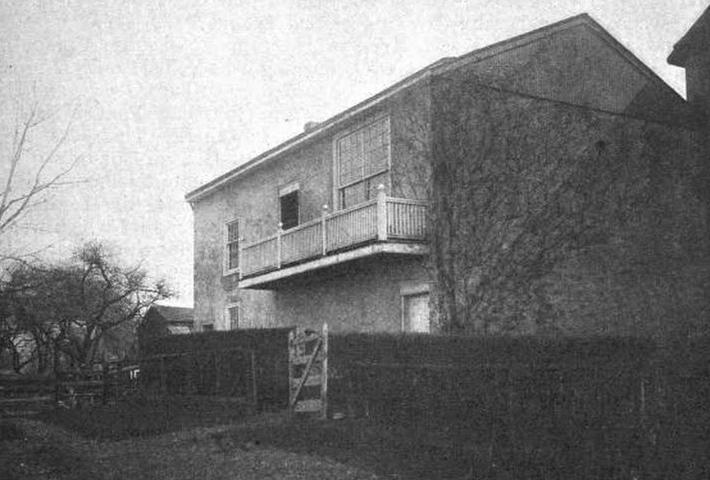

Abolition Hall is the building to the left in the above photograph. Maulsby Barn is the building to the right in this photo.

Please note that the “Village of Plymouth Meeting” is different from the postal designation of “Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania”. The Village is a small geographic area within the postal district of the same name.

Today, a substantial portion of Plymouth Township as well as a portion of Whitemarsh Township are known as “Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania”. In years past – not that long ago – much of that same area of Plymouth Township was known as “Norristown, Pennsylvania”. Other postal names have also been used through the years. For example, the area now part of the Plymouth Meeting Mall was designated for a time by postal officials as “Hickorytown, Pennsylvania”.

Some of the buildings and sites in the Village of Plymouth Meeting are protected as historical treasures because of their ownership and use. One example is the Plymouth Friends Meeting House. This house of worship is the home of the Plymouth Monthly Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends. This religious denomination is also known as the “Quakers”. It is the Plymouth Monthly Meeting that gave its name to the village.

Most of the buildings and real estate within the Village of Plymouth Meeting are privately owned. Even the site of the United States Post Office in Plymouth Meeting is privately owned.

Private landownership is one of the hallmarks of the United States of America.

Through the years, a number of vacant pieces of land within the Village of Plymouth Meeting – land that had previously been farmed, quarried, or used for other purposes – have been developed into office buildings and houses.

Few pieces of open space remain within the Village of Plymouth Meeting.

One of those pieces of property may soon be developed.

In a separate edition of The Freedom Valley Chronicles, the specifics of that potential development will be explored.

Three buildings at the intersection of Butler Pike and Germantown Pike have remained in common ownership for more than 175 years. Like other buildings within walking distance of this intersection, these three buildings have remained largely the same for generations.

The three buildings – Abolition Hall, Hovenden House, and Maulsby Barn – were jointly nominated to be added to the National Register of Historic Places on September 8, 1970. After a review, the three buildings were added as a group to this national registry on February 18, 1971. As of September of 2015, the National Park Service indicated that more than 90,000 properties are on the National Register of Historic Places.

Abolition Hall, Hovenden House, and Maulsby Barn occupy a small portion of a parcel of land comprising 10.45 acres. This piece of real estate is but a remnant of the lands initially owned by the Maulsby and Corson families. According to a news article dated December 6, 1918, in The Conshohocken Recorder, while the specific lands and specific ownerships have changed through the years, more than 100 acres of land were owned by these families in the area. In general, much of the ground between Cold Point and Germantown Pike along what we today call “Butler Pike” was owned at one time or another by the Maulsby and Corson families. The land was utilized for farming as well as industry. Limestone quarries and lime kilns as well as a coal business were active on these lands.

Abolition Hall was a center of the anti-slavery movement in the United States.

The building began modestly as a “one-storey open carriage house…three 18” stone walls with two 4’ diameter rubble and mortar pillars supporting the roof,” according to the nomination form for the three buildings to be considered for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.

The nomination form continued: “In 1856, the lower portion was enclosed and a full length hall added as a second storey.” This nomination form was prepared by Ms. Nancy Corson in her position as Treasurer of the Plymouth Meeting Historical Society in 1969.

Upwards of 200 people could attend meetings at Abolition Hall to listen to speakers and talk of ways to cleanse this nation of its original sin.

Slavery.

The Declaration of Independence speaks eloquently of “All men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

But the document that guided the actual government of the United States of America – the United States Constitution – was crafted as an operational document. As such, compromises were made from day one.

One of the more unusual compromises was the one that explicitly states that certain human beings were only 3/5th of a person.

Individuals in human bondage – slaves – were, sort of, a person. Just not a whole person.

From the earliest days of the union, there were those that saw the problem with this compromise.

In this area, members of the Religious Society of Friends and the Baptists were among those that saw slavery as an evil.

Not something to participate in. Not something to condone. Not something to accept.

But something akin to a cancer that had to be removed from the nation.

Quaker views have been intertwined with the Greater Philadelphia Area and with the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania for hundreds of years. Plymouth Township was founded by members of the Religious Society of Friends. Plymouth Meeting – including lands in both Plymouth Township and Whitemarsh Township – was one of the earliest European settlements in the region.

The Morning Call newspaper of Allentown, in a news article dated January 31, 1943, explained some of the reasons why Quakers stood tall then – as they do today – in their direct assistance to those in need: “Their concern for suffering men and women is rooted in a reverence for human personality. The slave, the prisoner, the exploited laborer, the under-privileged child, from the Quaker point of view, are human beings divinely endowed with the right of physical and spiritual fulfillment.”

Some of the earliest Quakers in Pennsylvania owned human beings as property. As slaves.

Through the early years of the Commonwealth, while Quakers and others came to the belief that slavery was wrong, people did not necessarily come to this belief because it was the “in” thing to do. It took time.

As most Americans are aware, a number of the founders of this nation owned human beings as slaves.

A few of those founders eventually realized that slavery was an evil.

For a time, Mr. Benjamin Franklin owned human beings as slaves. He made money off of the slave trade by selling advertisements in his publication, the Pennsylvania Gazette. Some of those ads were for the sale of human beings or for rewards being offered for the return of human beings who fled bondage.

Eventually, Mr. Franklin recognized that the concept and the reality of owning other human beings – though legal and acceptable to many in power – was not a moral choice.

According to the Library of Congress, Mr. Franklin appealed for public support to not only end slavery and the slave trade, but to educate the former slaves and their children.

According to the National Archives, Mr. Franklin became President of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery in 1787. His last public act, according to the Federal Government, was to send Congress a petition dated February 3, 1790, asking for an end to slavery and an end to the slave trade.

In 1790, the United States Congress declined to abolish slavery, end the slave trade, and provide freedom to the human beings owned by others.

It would be 18 more years – in 1808 – before a Congressional act made the importation into the United States of human beings as slaves officially a criminal act.

While importing human beings as slaves became illegal, the domestic sale of human beings became big business in the United States. In this country, children born to human beings in bondage themselves were slaves.

Laws were passed codifying that human beings fleeing bondage were fugitives from justice. That providing aid to these human beings – who were considered property of others – was illegal. Fines could be assessed to those who interfered in the ownership of such property. Jail terms were meted out to people who aided fugitive slaves.

Not all Americans agreed with these mores and with these laws.

Some of those Americans lived in Plymouth Meeting and the Freedom Valley.

Maulsby House – now known as the “Hovenden House” – as seen in a photograph from 1906. The white fence is no longer at the site. The photo was taken from the grounds of the Plymouth Friends Meeting House.

Mr. Charles Blockson, a noted historian, described the Village of Plymouth Meeting in his book, Hippocrene Guide to the Underground Railroad: “The entire village was abolitionist…It’s the most intact Underground Railroad village in my experience.”

“The Plymouth Meeting Anti-Slavery Society held its first meeting in the Friends Meeting House in 1833,” explained The Philadelphia Inquirer in a news article dated February 9, 1964. “Samuel Maulsby, leader of the Abolitionists in the community, presided at that first meeting…Later, threats of slave catchers and anti-Abolitionists to burn the building caused the followers of Maulsby to hold clandestine meetings in neighborhood homes.” [Please note that this news article may actually be referencing the Montgomery County Anti-Slavery Society.]

While there were churches, schools, and other buildings in the area that had space for meetings, few of those organizations were willing to allow the abolitionists – people opposed to slavery – to meet within their buildings. Through the years, the few places that did allow such meetings initially, stopped that practice.

The Courier-Post of Camden County in a news article dated February 21, 1999, noted that “Not all Quakers agreed on this subject [abolition of slavery], and the Plymouth Meeting House would not allow anti-slavery discussion.”

People then met in small groups in private homes. Quietly.

Mr. George Corson decided to change the dynamics of the movement.

It was he who expanded his carriage house into Abolition Hall in 1856. This meeting place was designed so that anti-slavery advocates could meet in peace.

Abolition Hall, also known as “Anti-Slavery Hall”, was built explicitly for the purpose of people meeting to advocate for the freedom of men, women, and children held in bondage within the borders of the United States of America.

According to a news article in The Conshohocken Recorder dated January 28, 1927, “…George Corson built the hall that was a center of the anti-slavery movement for many years when churches and public halls were closed to the abolitionists.”

He – and others – made it clear that their message of freedom would not be silenced. They would not be quiet. They would hold firm to the words of the Declaration of Independence: “All men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness.”

The deeds of Mr. Corson were noticed by people far and wide. By slaves. Slave owners. Fellow Quakers. Political leaders. Ordinary citizens.

In a news article dated December 3, 1915, The Conshohocken Recorder reported some of the speakers who visited Abolition Hall: “In it were heard during the succeeding years such forceful abolition agitators as [William Lloyd] Garrison, [James Miller] McKim, the Burleighs [Margaret Jones Burleigh and Charles Calistus Burleigh], Lucretia Mott, Abbie Kelley [Abby Kelley Foster], Mary Greer [Mary Grew], and others hardly less powerful in the sweeping and humane movement.”

A separate edition of The Freedom Valley Chronicles will detail some of these individuals who spoke at Abolition Hall.

Through the years, there have been stories detailing a tunnel or tunnels that are connected to Abolition Hall. Those stories are false. “There are no tunnels at Abolition Hall,” stated Mr. Roy Wilson who has lived on the property for decades. “There is a root cellar on the property, but slaves were not hidden in the root cellar. Food was kept in the root cellar.”

The history of the Underground Railroad in Plymouth Meeting has been noted by many – far and wide.

Hovenden House – previously known as the “Maulsby House” – and Maulsby Barn were two of the places within the Village of Plymouth Meeting that served as hiding places for human beings fleeing slavery.

In a news article dated May 19, 1884, The Hartford Courant reported that “this house was one of the ‘underground railroad stations’ in the times when fugitive slaves were sheltered by anti-slavery men.”

According to The Philadelphia Inquirer in a news article dated February 9, 1964, even prior to the formation of an anti-slavery society, Mr. Maulsby and others in the Corson family spoke “openly against slavery as early as 1820.” Mr. Maulsby routinely hid slaves in his home – now called the “Hovenden House” – and his barn at Butler and Germantown Pikes.

Mr. Blockson is quoted in a news article dated June 19, 1995, in The Philadelphia Daily News that “slaves hid in the attic [of Hovenden House] where they could look out of those windows and see what was coming up Germantown Pike.”

The Courier-Post of Camden County in a news article dated February 21, 1999, noted that the “Maulsby House was…a safe house for fugitive slaves who were hidden in the attic, behind the tiny dormer windows that overlook Germantown Pike.”

In the small town of Estherville, Iowa, a news article dated October 2, 1895, in the Estherville Democrat, note was made of the “Plymouth meeting barn which was once a station of the old underground railroad…in which fugitive slaves had been sheltered.”

On May 18, 1884, a news article in The Sunday Inter Ocean in Chicago, noted the efforts of Mr. Corson as a leader of “one of the ‘underground railway stations’ where fugitive slaves were sheltered by sympathizers on their perilous journey northward to Canada.”

According to a news article dated December 19, 1900, in The Leavenworth Times in Kansas, speaking of Mr. Corson: “He not only was a pronounced Abolitionist himself, but he had a hall built in which those doctrines could be preached. This building is still standing…”

A number of members of the Corson family shared the beliefs and activities of Mr. George Corson. The December 24, 1895, issue of The Conshohocken Recorder noted the “appreciative resume” of Dr. Hiram Corson: “…The Norristown Herald speaks of his antagonism to slavery and of his active efforts to free the slave, efforts well remembered by the older citizens of Pennsylvania.”

According to a news article dated May 26, 1884, in The Philadelphia Inquirer, the efforts of the Corson family were not universally welcomed. This news article stated that “…the Corsons…ever held in high esteem except during the days when anti-slavery sentiments were regarded as next door to treason.”

In the years after the American Civil War, Abolition Hall was utilized as an art studio. Mr. Thomas Hovenden and Ms. Martha Hovenden were among the artists that have created art in this structure. Artwork produced at Abolition Hall can be seen in museums and public places from the City of New York to Valley Forge and from Harrisburg to Washington, District of Columbia.

The structure of Abolition Hall seen today may well have been partially rebuilt after a fire that hit this property on August 13, 1901.

Though no one has been able to confirm it on the record, it is likely, based on two separate news articles, that it was the building that is now called “Abolition Hall” that burned on that August date – not what is called today the barn – Maulsby Barn – on this property.

On August 31, 1901, The New York Times reported that a $300.00 reward had been offered for “information leading to the arrest and conviction of the person or persons who set fire to the barn of the undersigned at Plymouth Meeting, Pa., on the night of August 13th.” The newspaper reported that the offer was made by Ms. Helen Corson Hovenden.

The news article notes that “The burning of a barn is such an ordinary occurrence in all rural districts that only some decidedly unusual feature could prompt the owner to offer so large a reward for the discovery of the incendiaries. And the old barn at Plymouth Meeting, twelve miles from Philadelphia, had associations that were unusual and undoubtedly unique, for it was the studio wherein Thomas Hovenden painted ‘Breaking Home Ties’ and other famous pictures, while before he secured it the structure served as a station in the ‘underground railroad’ whereby prior to the civil war fugitive slaves sought to attain freedom.”

This news article also noted that “…the place was allowed to remain almost as it was when the artist’s [Mr. Hovenden’s] brush made the last stroke. Consequently, many relics and art treasures gathered in all parts of the world were lost by the destruction of the building.”

On August 16, 1901, The Buffalo Express reported that “the unique studio which was built by the famous artist, Thomas Hovenden, at Norristown [Plymouth Meeting], and in which he did his best work, was burned on Wednesday.”

In a news article dated August 14, 1901, The Reading Times reported of a large barn fire by Ms. Helen Hovenden on August 13, 1901. The news article indicated that 3 horses died; a fourth horse was rescued. This newspaper indicated that because the crops had recently been harvested “it is supposed that spontaneous combustion was the cause.” The loss was estimated at $5,000.00, including for farm implements and the animals.

Further information on Abolition Hall, Hovenden House, and Maulsby Barn will be detailed in future editions of The Freedom Valley Chronicles.

The top photo of Abolition Hall and Maulsby Barn is courtesy of Mr. Roy Wilson, 2018.

The second photograph of Abolition Hall is courtesy of Ms. Phebe Westcott Humphreys, 1909.

The third photograph of Abolition Hall is courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places, 1969.

The first photograph of Hovenden House, also known as Maulsby House, is courtesy of Dr. Hiram Corson, 1906.

The second photograph of Hovenden House, also known as Maulsby House, is courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places, 1969.

The first photograph of Maulsby Barn is courtesy of the National Register of Historic Places, 1969.

The second photograph of Maulsby Barn is courtesy of Smallbones via Wikipedia, 2011.

Do you have questions about local history? A street name? A building?

Your questions may be used in a future news article.

Contact Richard McDonough at freedomvalleychronicles@gmail.com.

© 2018 Richard McDonough