Sometimes a building is not just a structure.

Sometimes a piece of land is not just a parcel of real estate.

Sometimes a building or site becomes a symbol.

A memorial.

A monument.

To an event.

To an activity.

To an ideal.

In the United States, memorials and monuments are generally created by those who want others to remember things that they deem important at that time. Not necessarily at the time of occurrence by contemporaries, but in many situations, years – many years – later.

For example, most people traveling today through the national park at Valley Forge might assume that those lands were always protected as part of a national park. Yet it was only in 1976 when the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania donated the Valley Forge State Park to the Federal Government. That state park was only formally established in 1893 – more than 100 years after the winter encampment at Valley Forge of 1777-78. For much of the time after the American Revolutionary War, the land at Valley Forge was in private ownership. Even today, some of the real estate that comprises the lands of the encampment remain in private ownership.

As has been the case with all of the historical buildings in the Village of Plymouth Meeting, Abolition Hall has been maintained by private ownership through the generations.

Built by Mr. George Corson from an existing carriage house on his property in 1856, the structure known as “Abolition Hall” was likely only used for anti-slavery efforts for, perhaps, 5 years or, at most, 9 years.

But whether it was 5 years, 9 years, or some other length of time, it’s important to remember the circumstances that led Mr. Corson to build an Abolition Hall and for others to come to Plymouth Meeting to speak at this structure.

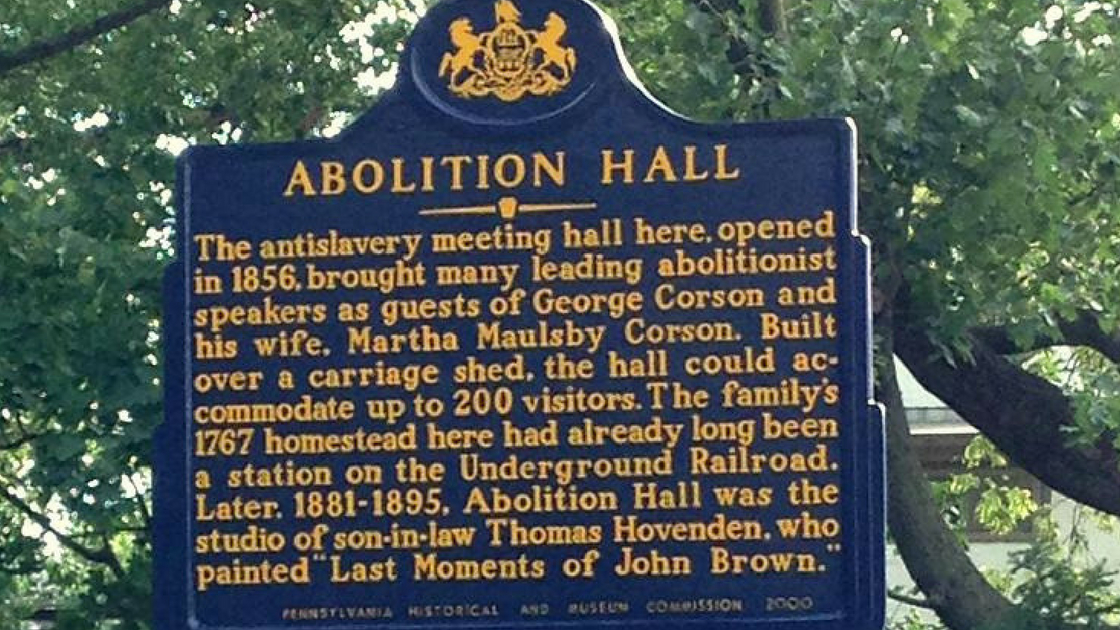

To recognize the historic significance of this building as well as the role of the Corson family in helping human beings escape bondage and attain freedom through the Underground Railroad, the Commonwealth approved the placement of an historic marker for Abolition Hall at 4006 Butler Pike. The marker, seen in the photograph above, was dedicated on November 18, 2000.

One should never forget that the United States of America was a very different place in 1856 from what it is today.

One needs to remember what reality was in those days.

An African-American man in Alabama could not vote in an election.

An African-American man in Pennsylvania could not vote in an election.

Pennsylvania – the home of the Liberty Bell and Independence Hall – had changed its constitution in 1838. The new constitution stated that only certain White men could vote in elections in the Commonwealth.

From the “Texts of the Constitution” section of the website of Duquesne University, the wording of a section of Article III of the 1838 Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is as follows:

Section I. In elections by the citizens, every white freeman of the age of twenty-one years, having resided in the State one year, and in the election district where he offers to vote, ten days immediately proceeding such election, and within two years paid a State or county tax, which shall have been assessed at least ten days before the election, shall enjoy the rights of an elector. But a citizen of the United States who had previously been a qualified voter of this State, and removed therefrom and returned, and who shall have resided in the election district, and paid taxes, as aforesaid, shall be entitled to vote after residing in the State six months: Provided, That white freemen, citizens of the United States, between the ages of twenty-one and twenty-two years, and having resided in the State one year and in the election district ten days, as aforesaid, shall be entitled to vote, although they shall not have paid taxes.

Compare that wording in Article III of the 1838 Constitution to the same Article III previously in force in Pennsylvania. Again, from the “Texts of the Constitution” section of the website of Duquesne University, the wording of a section of Article III of the 1790 Constitution of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania is as follows:

Section I. In elections by the citizens, every freeman of the age of twenty-one years, having resided in the state two years next before the election, and within that time paid a state or county tax, which shall have been assessed at least six months before the election, shall enjoy the rights of an elector: Provided, that the sons of persons qualified as aforesaid, between the ages of twenty-one and twenty-two years, shall be entitled to vote, although they shall not have paid taxes.

(Both constitutions did not give women of any race the right to vote. Wyoming was the first state or territory in this nation to give women the right in vote in 1869. Nationally, women did not get the right to vote in all elections until the 19th Amendment to the United States Constitution was ratified. That occurred in 1920. Less than 100 years ago.)

Voting rights was just one difference between now and then.

The Philadelphia Inquirer explained in a news article dated February 9, 1964, why hiding slaves in “one’s home entailed great risk…Agents of slaveowners watched … homes day and night. With the passing of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850, lending aid to a fleeing slave became a penal [criminal] offense.”

It wasn’t just private residences that were at risk.

Churches and religious institutions were also at great risk.

On May 13, 1888, The Philadelphia Times reported of several churches that were attacked because the congregations had allowed abolitionists to speak in their buildings. On July 4, 1834, this newspaper article reported that Chatham Street Chapel in the City of New York was attacked by a mob. The same newspaper article stated “In Philadelphia, the first riots against Abolitionists and the colored people took place in August of 1834, when a meeting house, near Wharton Market was torn down and many colored people assaulted and their houses broken into.”

The First Baptist Church of Norristown, located to the left of the Montgomery County Court House (the white building with a dome) in this photograph, was attacked because the congregation allowed abolitionists to speak at its building.

One Montgomery Plaza now stands at the former site of the First Baptist Church of Norristown at Swede Street and Airy Street in Norristown.

A news article dated December 19, 1900, in The Leavenworth Times in Kansas detailed some aspects of the Underground Railroad “some sixty years” earlier. One of the occasions noted by the newspaper was when the First Baptist Church of Norristown was attacked for allowing abolitionists to speak in their building: “At the close of one of their meetings the church was stormed by a mob and stoned.” The church was then located at Airy Street and Swede Street, the current site of One Montgomery Plaza.

While one might think that if a fugitive slave got past the Mason-Dixon Line, freedom was assured, one would be wrong. Very wrong. Not all fugitive slaves escaped north to Canada. A number were captured and returned to their owners in the South. Substantial numbers of people in the North – not just in the South – were against the abolition of slavery.

Here are three stories – unrelated to each other – but together they provide a vivid picture of what reality was in the time period that created the need for an Abolition Hall.

Story One: The Southern ‘Gentleman’ And The Negro

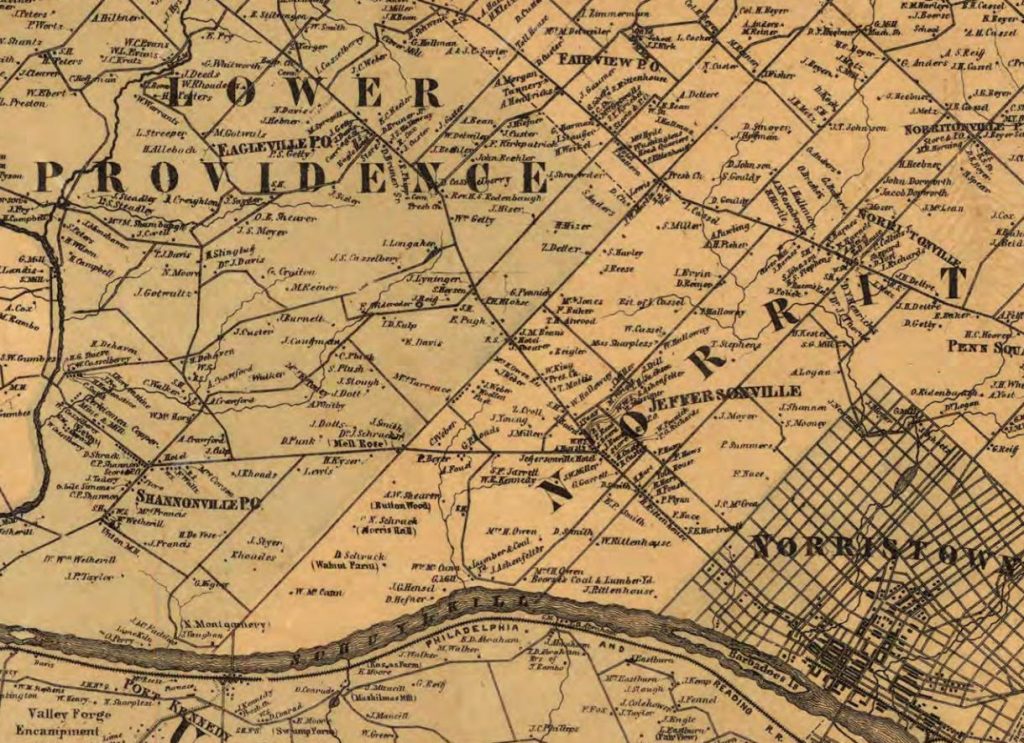

Shannonville is seen in the lower left-side of this map. Today, the village is known as “Audubon”. Norristown is seen in the lower right-side of this map. Mr. George Corson was traveling east of Shannonville when he came upon a slave owner on horseback and a human being held as a slave walking alongside the horse.

According to a news article dated December 19, 1900, in The Leavenworth Times in Kansas, “George Corson once got himself prominently in the public eye through a legal set-to with a slave owner whom he passed in the road. The white man sat on his horse leading the walking negro by a rope around the colored man’s neck. The sight made George Corson’s blood boil, and when the man had gotten his horse and slave secured in the stable of a Norristown hotel, he was confronted with a warrant of arrest secured on Mr. Corson’s information.”

“Of course public sympathy and the magistrate were with the southern ‘gentleman,’ and the result was that the prosecutor was compelled to pay the costs, besides being made the subject of the town’s indignation. But times have changed in the few years that have passed and we of this generation can look upon those ardent leaders of the anti-slavery cause from a different point of view than did their contemporaries.”

The History of Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, Volume 2, confirmed the essence of this news story. The book stated that Mr. Corson was riding on his horse “on the back road east of Shannonville” (today known as “Audubon”). The book confirmed that “The magistrate decided that ‘the master had a right to his property…’”

Story Two: A Trip To Maryland

Independence Hall in Philadelphia was the site of a court hearing where a resident of Philadelphia was sent to Maryland to potentially be re-enslaved as property.

A news article printed on January 1, 1851, in The Wilkes-Barre Advocate detailed how one man almost lost his freedom because he was a Black man: “Recently, a colored man named Adam Gibson, was arrested in Philadelphia, alleged to be Emery Rice, a Fugitive Slave belonging to Mr. Knight, in Maryland. An examination was had before Commissioner Ingraham, who remanded the alleged Fugitive, and he was conveyed to Elkton, Maryland, and kept in jail until Mr. Knight arrived, who, on seeing him, said he was not his slave, and the poor fellow was permitted to return to his wife and child in Philadelphia. It is worthy of remark that Mr. Knight cautioned Adam against an individual, telling him if he was not careful, the man would sell him before he got out of Maryland. On his return to the city [of Philadelphia] a man attempted to arrest him, from whom he made his escape.”

The Baltimore Sun, in a news article dated December 23, 1850, detailed the initial part of this event: “Adam Gibson, an alleged fugitive slave from Cecil county, Md., was arrested to-day and had a hearing before the U. S. commissioner, Edward D. Ingraham, Esq. The alleged slave is claimed by Wm. Knight, of Cecil county, Md., as Emery Rice, a slave belonging to him, who escaped in 1841, and must now be 35 years old. The prisoner does not appear to be more than 25 years old, and the witnesses brought forward in his behalf testify that his name is Adam Gibson, and that he belonged to the late Parson Henry Davis, deceased, by whose last will he was set free in 1840. A certified copy of the will was produced as evidence of this fact. The case was argued by Wm. E. Lehman, Esq., for the claimant, and William S. Pierce and David Paul Brown, Esqs., for the prisoner. The speech of the latter was a most brilliant effort, abounding in bitter invective against the parties engaged in the arrest of the fugitive. The commissioner, however, deemed the evidence of identity sufficient, and ordered him to be remanded to the custody of his owners. A large crowd of colored persons assembled in front of the Hall of Independence, where the hearing took place, but they remained perfectly passive, and occasioned no noise or disturbance. They continued there up to the present time (9 o’clock, P. M.,) [on December 21, 1850] in the expectation of seeing him removed, but to avoid any difficulty he has been taken out the back way.”

Story Three: A Barber Says “No”

On July 2, 1851, The Wilkes-Barre Advocate reported that “Jesse, the Fugitive Slave, who was adroitly captured in this Borough [of Wilkes-Barre], on Saturday, 21st ult. [this means “last month”], was met by the man who claimed him as his slave, at Hazleton. It is said they were glad to see each other. Jesse promised that he would not abscond again, and his master promised he would not sell him.”

At least one man was not accepting of this transfer. The Wayne County Herald in Honesdale in a news article dated July 10, 1851, noted that “A negro barber, named Mason, was arrested in consequence of threatening to kill several of the citizens, for taking part in arresting ‘Jesse,’ the fugitive slave. Mason, on his way to prison, in custody of constable Johnson, attacked him with a razor, cutting his (Johnson’s) face very badly…The negro was secured and lodged in jail.”

Summary:

Imagine your church or meetinghouse being stormed, stoned, and/or destroyed because you allowed someone to speak of the evil of slavery. That was the reality in places like the City of New York, Philadelphia, and Norristown.

Imagine trying to free a man from bondage in Norristown and being told by the courts that you had no right to do such a thing. And that most (though not all) of the area residents thought you a fool, at minimum, and treasonous, at worst. That was the reality in the Freedom Valley in the years leading to the American Civil War.

Imagine living as a free man in the City of Philadelphia and being arrested. Imagine that arrest leading to a hearing at Independence Hall where a judge decides to send you to Maryland to a man who claims you as his property. There is a real possibility that you will be re-enslaved. In 1850-51, this was not a movie; it was real life.

Imagine escaping slavery, getting as far as northeastern Pennsylvania (on your way to Canada where you would be free), and then getting caught. Imagine that it would be reported that you were glad to see your owner. That you would agree not to run away again and that your owner would agree not to sell you.

This was the reality in Pennsylvania in the years leading to the American Civil War.

This was the reality that Mr. Corson and other abolitionists faced when Abolition Hall was built and utilized as a forum to speak of the evil of human bondage.

The photograph of the historic marker for Abolition Hall is courtesy of Ms. Sydelle Zove, 2016.

The image of the Pennsylvania Coat of Arms is courtesy of by Mr. Henry Mitchell in The State Arms of the Union, 1876.

The aerial photograph of Norristown was taken by Aero Service Corporation and is courtesy of The Library Company of Philadelphia, 1922.

The photograph of One Montgomery Plaza is courtesy of Montgomery County, 2010.

The image displayed of Shannonville and Norristown is a portion of a map from 1861 courtesy of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission.

The photograph of Independence Hall was created by Ms. Carol M. Highsmith and is courtesy of the Library of Congress, 1980.

Do you have questions about local history? A street name? A building?

Your questions may be used in a future news article.

Contact Richard McDonough at freedomvalleychronicles@gmail.com.

© 2018 Richard McDonough