Thanksgiving today is considered a truly American holiday that is celebrated by almost everyone within the country.

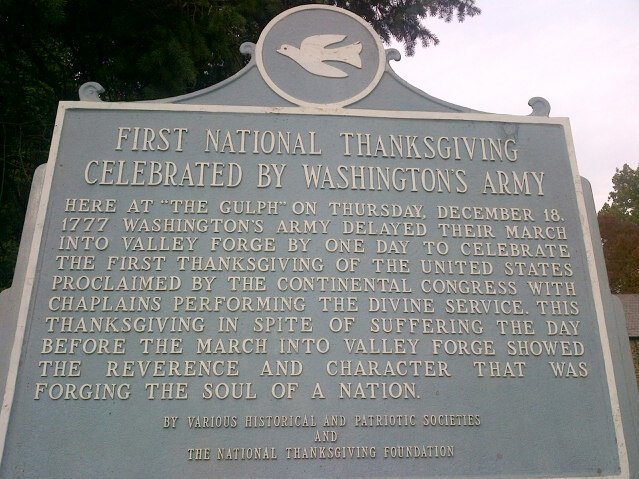

While the initial Thanksgivings by European settlers within the borders of what is now the United States likely took place in 1619 in Virginia and in 1621 in Massachusetts, the first national day of Thanksgiving – one set by a Congress of the United States – took place in Gulph Mills on December 18, 1777.

Most Thanksgiving celebrations were based on harvests, cultural traditions, and religious celebrations. Today, the date set aside for Thanksgiving – the fourth Thursday of November – was based on business considerations.

For decades in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, Thanksgiving was the last Thursday in November. In some years, that meant the time between Thanksgiving and Christmas was a week longer than in other years. In 1939, President Franklin Roosevelt declared the fourth Thursday of November to be Thanksgiving so as to lengthen the shopping season between Thanksgiving and Christmas.

“The event shown in this painting is the surrender of British General John Burgoyne at Saratoga, New York on October 17, 1777,” according to a statement from the Architect of the Capitol. “Burgoyne’s surrender followed battles with American General Horatio Gates near Saratoga in September and October 1777. With the British losing men and defenses during both engagements, Burgoyne retreated with a weakened army to Saratoga, where he surrendered to General Gates. This turning point in the American Revolution prevented the British from dividing New England from the rest of the colonies, and it was the deciding factor in bringing active French support to the American cause.”

The first official Thanksgiving in the United States was held on December 18, 1777, and was based on victory over the British during the Battle of Saratoga, in New York State, on October 17, 1777.

This fact is confirmed by a number of sources, including a news article dated November 22, 1942, in The Cincinnati Enquirer, in which the newspaper reported that “The first such national observance [of Thanksgiving] was held on December 18, 1777, virtually two months after the surrender of [British General John] Burgoyne at Saratoga, while Washington’s little army was freezing at Valley Forge [actually, at Gulph Mills].”

The Vermont Union Whig of Rutland, Vermont, in its newspaper dated December 6, 1848, re-printed a news article from the Cleveland Herald regarding the first official Thanksgiving in the United States:

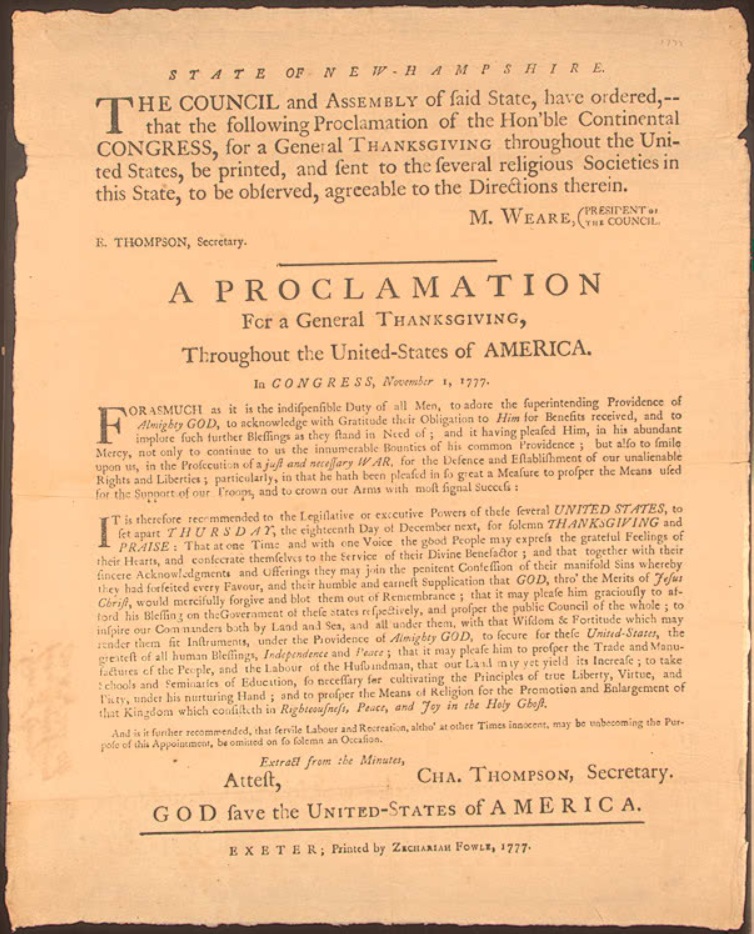

“During the troublesome days of the Revolution, our patriot fathers found cause for thanksgiving, and the ‘Continental Congress,’ at least twice, appointed by proclamation, a day for thanksgiving and praise. One of them was the 18th of December, 1777. The army was then at Valley Forge [actually, in Gulph Mills], and the Orderly Book of December 17, contains the following:

‘To-morrow being the day set apart by the honorable Congress for public thanksgiving and praise, and duty calling us devoutly to express our grateful acknowledgements to God for the manifold blessings he has granted us, the General [George Washington] directs that the Army retire to its private quarters, and that the chaplains perform divine service with their several corps and brigades; and earnestly exhorts all officers and soldiers, whose absence is not absolutely necessary, to attend with reverence the solemnities of the day.’”

The circumstances were poor for the soldiers in Upper Merion Township and throughout the Freedom Valley at that time.

The grave situation in Gulph Mills was described in a news article dated June 14, 1903, in the New-York Tribune: “For details of their suffering one can look here and there into the old diaries of the brave men who spent the winter there. Surgeon [Albigence] Waldo, of the 11th Connecticut Militia, wrote: ‘December 18 – Universal thanksgiving – a roasted pig to-night. The army are poorly supplied with provisions, owing it is said, to the neglect of the commissary of purchases. The Congress have not made their commissions valuable enough. Heaven avert the bad consequences of these things.’”

The National Park Service quoted two diaries of members of the Continental Army indicating that not every soldier enjoyed this first Thanksgiving. Sergeant Ebenezer Wild of the First Massachusetts Regiment stated that “We had but a poor Thanksgiven, Nothing but Fresh beef and Flour to Eate Without aney Salt & but very Scant of that.”

“We had nothing to eat for two or three days previous, except what the trees of the fields and forests afforded us. but we must now have what Congress said, a sumptuous Thanksgiving to close the year of high living we had now nearly seen brought to a close,” stated Mr. Joseph Plumb Martin of the Eighth Connecticut Regiment. “And what do you think it was ? …it gave each and every man half a gill of rice and a tablespoonful of vinegar!”

According to the National Park Service, “one half-gill equals two ounces. The commissary often issued vinegar to the soldiers for use as a purifier and scurvy preventative. The men mixed the vinegar with canteen water rather than drink it full strength.”

Another diary passage was quoted in a news article dated November 25, 1908, in The Buffalo Commercial: “December 18, 1777 – the day before the Continental army went into winter quarters at Valley Forge – Lieutenant Colonel Henry Dearborn made this entry in his diary: ‘This is the Thanksgiving Day through the whole Continent of America, but God knows we have been without flour or bread, and are living on a high, uncultivated hill, in the huts and tents, and lying on the cold ground. Upon the whole I think all we have to be thankful is that we are alive and not in the grave with many of our friends. We had for Thanksgiving breakfast some exceedingly poor beef which has been boiled and now warmed in an old short-handled frying-pan, in which we were obliged to eat it, having no other platter. I dined and supped with General Sullivan today, and so ended Thanksgiving.’”

For all its difficulties, the First Thanksgiving showcased a willingness to preserver even in circumstances exceedingly poor.

The Tampa Tribune reported in a news article dated November 22, 1907, that “In those early days the founders of the republic were wont to bestow much more attention upon the observance of Thanksgiving than was accorded Christmas, particularly in the matter of the feast. It was during the Revolutionary War that the custom of setting apart days of thanksgiving which had previously been confined largely to New England spread to other parts of the country, for during the struggle for independence the Continental Congress recommended no less than eight days of thanksgiving.”

The image of the painting of the surrender at Saratoga was painted by Mr. John Trumbull in 1821, placed in the Rotunda of the United States Capitol in 1826, and is provided courtesy of the Architect of the Capitol, 1821.

The photograph of the commemorative marker is provided courtesy of Trinity Episcopal Church, 2013.

The image of the Thanksgiving Proclamation by the Continental Congress is provided courtesy of the National Archives, 1777.

Do you have questions about local history? A street name? A building?

Your questions may be used in a future news column.

Contact Richard McDonough at freedomvalleychronicles@gmail.com.

© 2018 Richard McDonough