You may have read news articles recently about sinkholes. A portion of Butler Pike is still closed to through traffic from Flourtown Road to Germantown Pike in Plymouth Meeting because of a sinkhole that opened in early August of this year. On March 19, 2018, a sinkhole opened adjacent to Crooked Lane in the King Manor section of Upper Merion. In King of Prussia, a sinkhole opened on Shaffer Road, just off of DeKalb Pike, about a year ago on September 5, 2017.

News articles like these are, unfortunately, not new.

Ever wonder why DeKalb Street in Bridgeport curves into DeKalb Pike in Upper Merion? It’s because parts of DeKalb Pike fell into a large sinkhole years ago on January 25, 1971.

On April 2, 1971, The Morning Call of Allentown reported that there had been two additional sinkholes that had appeared in the same area since late January of that year. As of April 11, 1971, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that PennDOT had attempted to repair the sinkholes five times by filling them with tons of materials. In a news article dated June 15, 1971, The Morning Call reported that the seepage into the sinkholes had been between 48 feet and 75 feet deep. On October 6, 1971, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that another sinkhole had opened on this stretch of road two days earlier.

Almost three years after the initial sinkhole opened at this location between the two municipalities, the sinkholes were still causing problems. In a news article dated December 16, 1973, The Philadelphia Inquirer reported that PennDOT was spending $4.8 million to repair the series of six sinkholes that had opened since January of 1971 on this specific section of DeKalb Pike. The newspaper quoted one PennDOT official as stating that one of the sinkholes had been 50 feet in diameter.

You may ask – What exactly is a sinkhole and how is it caused?

“A sinkhole is a depression in the ground that has no natural external surface drainage,” according to a statement from the United States Geological Survey (USGS) of the Department of the Interior. “Basically this means that when it rains, all of the water stays inside the sinkhole and typically drains into the subsurface.”

“Sinkholes are most common in what geologists call ‘Karst Terrain’,” continued a statement from the USGS. “These are regions where the types of rock below the land surface can naturally be dissolved by groundwater circulating through them. Soluble rocks include salt beds and domes, gypsum, and limestone and other carbonate rock. When water from rainfall moves down through the soil, these types of rock begin to dissolve. This creates underground spaces and caverns. Sinkholes are dramatic because the land usually stays intact for a period of time until the underground spaces just get too big. If there is not enough support for the land above the spaces, then a sudden collapse of the land surface can occur.”

Thus, a sinkhole.

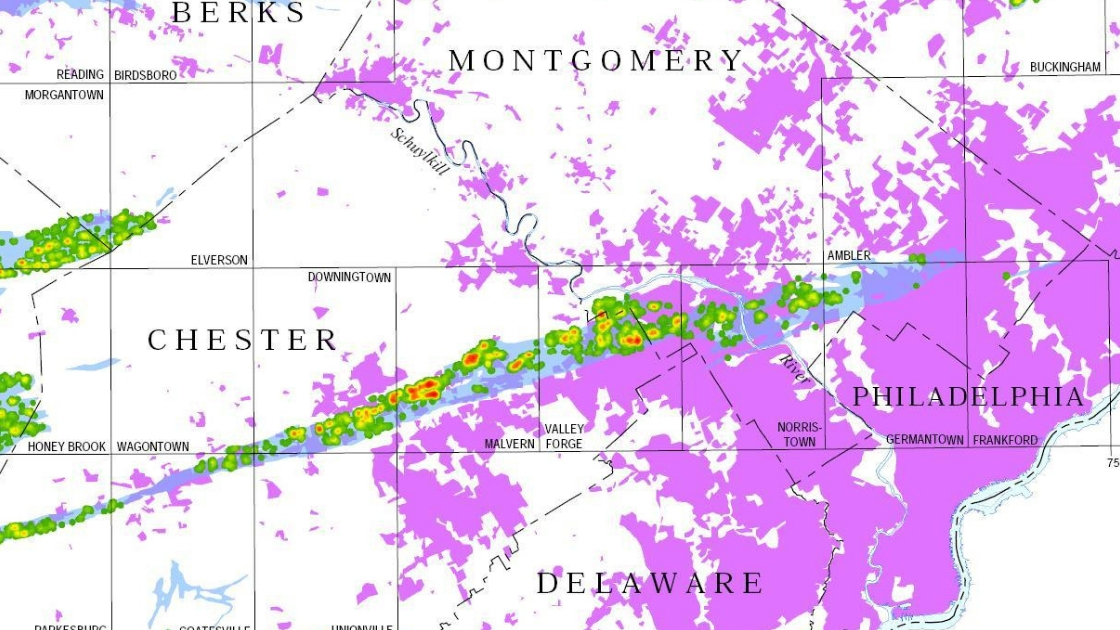

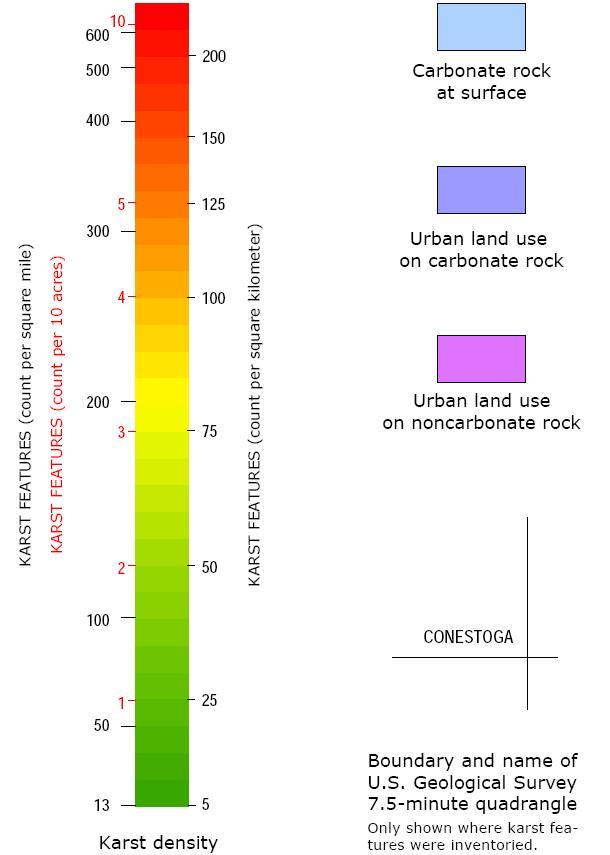

The map above shows the concentration of a band of sinkholes and ground that is prone to sinkholes from southern Chester County through the Freedom Valley in Montgomery County. The oranges, yellows, and greens are areas with Karst Features. The areas colored purple are considered less prone to sinkholes. The legend below provides greater details of what the colors represent on the map.

The map above shows the concentration of a band of sinkholes and ground that is prone to sinkholes from southern Chester County through the Freedom Valley in Montgomery County. The oranges, yellows, and greens are areas with Karst Features. The areas colored purple are considered less prone to sinkholes. The legend below provides greater details of what the colors represent on the map.

Much of the land identified with Karst Features includes ground that is composed of limestone. Other concentrations of ground with Karst Features identified on this map are in Lancaster County, to the left on the map, as well as an area in Chester County north of the State of Delaware.

The map above shows the extent of sinkholes in sections of the Freedom Valley that include Upper Merion, Plymouth, and Whitemarsh Townships as well as Conshohocken and West Conshohocken Boroughs. The oranges, yellows, and greens highlight areas known for sinkholes as well as ground that is prone to formation of sinkholes. The areas colored purple are considered less prone to sinkholes. The legend above provides greater detail on what the colors mean on this map.

The concentration of oranges, yellows, and greens to the left in the map includes the communities of King Manor, King of Prussia, Swedeland, and Gulph Mills. The concentration of yellows and greens in the middle of this map includes the Ivy Rock and Seven Stars areas of Plymouth Township as well as neighborhoods in the Colwell Lane area of the Township. The concentration of the oranges, yellows, and greens to the right of the map includes the communities of Plymouth Meeting, Cold Point, and Lafayette Hill.

According to the “Open Space, Natural Features, and Cultural Resources Plan – Shaping Our Future – A Comprehensive Plan for Montgomery County”, issued by Montgomery County in 2005, the geology of sections of the County includes a strong concentration of Ledger Dolomite, Elbrook, and Conestoga Limestone.

The report stated that “These [geological formations] form a limestone valley that extends eastward from Lancaster County through Chester County, tapering off within Abington Township. The soils formed from this parent material are fertile, and the groundwater yields are good when wells are located within fractured rock. The limestone and dolomite formations yield good trap rock and calcium rich rock which has been quarried for various industrial and construction uses.”

As for sinkholes, the report from Montgomery County stated that “Sinkholes can form in the limestone formation when water dissolves portions of the rock resulting in underground cavities…Care must be taken in the development of buildings and the management of stormwater in these locations.”

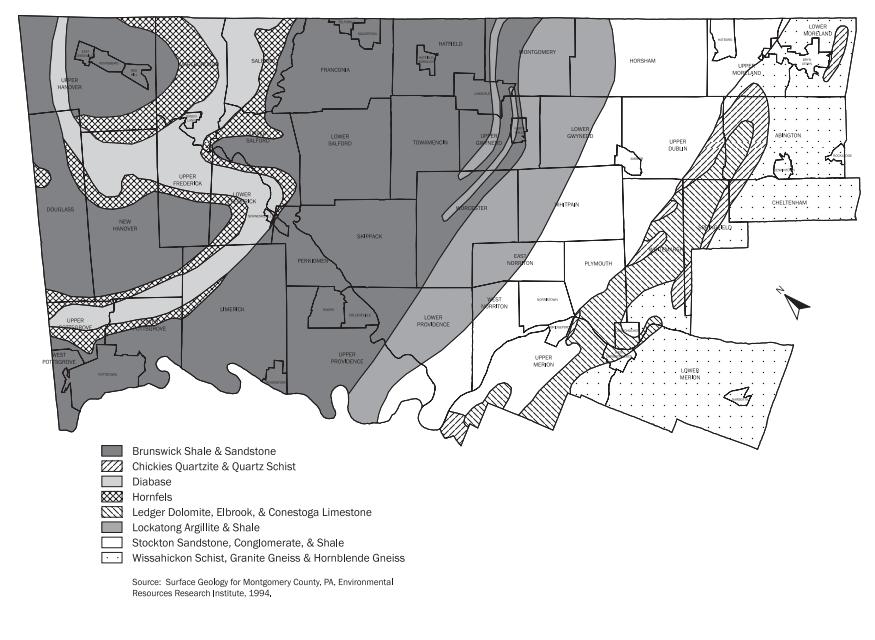

The map above of Montgomery County is from the “Open Space, Natural Features, and Cultural Resources Plan Shaping Our Future – A Comprehensive Plan for Montgomery County”, issued by Montgomery County in 2005. This map highlights that about half of Plymouth Township and West Conshohocken Borough, the bulk of the Borough of Conshohocken, and substantial portions of Whitemarsh Township are atop Ledger Dolomite, Elbrook, and Conestoga Limestone geology formations.

The map above of Montgomery County is from the “Open Space, Natural Features, and Cultural Resources Plan Shaping Our Future – A Comprehensive Plan for Montgomery County”, issued by Montgomery County in 2005. This map highlights that about half of Plymouth Township and West Conshohocken Borough, the bulk of the Borough of Conshohocken, and substantial portions of Whitemarsh Township are atop Ledger Dolomite, Elbrook, and Conestoga Limestone geology formations.

You can view the entire section of this comprehensive plan of Montgomery County by clicking here.

This series of news columns on sinkholes will continue with additional information about these geological formations in The Freedom Valley Chronicles – Sinkholes Part 2. Part 3 of the news columns will focus on one major infrastructure project that cost more than $2 million to rebuild because of a sinkhole. Part 4 of this series of The Freedom Valley Chronicles will focus on a proposed housing development in Plymouth Meeting. Insurance options for homeowners wanting to get coverage for potential sinkhole dangers will be highlighted in Part 5 of the series of news columns.

The first two maps and the associated legend are courtesy of the Pennsylvania Geological Survey, officially known as the Pennsylvania Department of Conservation and Natural Resources Bureau of Topographic and Geologic Survey, 2003.

The bedrock geology map of Montgomery County is courtesy of Montgomery County, 2005.

Do you have questions about local history? A street name? A building?

Your questions may be used in a future news column.

Contact Richard McDonough at freedomvalleychronicles@gmail.com.

© 2018 Richard McDonough